DUBAI // Long before the days of oil and skyscrapers, coastal villagers living off the sea warned their sailors to beware of the djinn Baba Darya. A menace to fishermen and pearl divers, the water demon stalked ships and plundered them for the day's haul of pearls while the crewmen slept. Most terrible of all, the hungry Baba Darya - the "Father of the Sea" - was said to creep on board to drag away sleeping sailors and eat them alive.

According to folklore, few ever saw the creature long enough to study its face in the darkness, but by all accounts it was a frightful sight. To protect themselves and their pearls, the seafarers began watching and listening for signs that Baba Darya was stirring in the black waters below. That was enough to discourage the spirit from causing any more mischief. And over time, it became customary among local sailors for two or three men to guard the deck each night.

Or, at least, so goes one version of the bogeyman myth. "There could be many, many different versions," said Dr Khalid Salem al Dhaheri, the director of the National Library at the Abu Dhabi Authority for Culture and Heritage (Adach). "Baba Darya is a spirit that is said to enchant the oceans of the Gulf. Of course the different takes on this tale depends on the imagination of who recites it." Dr al Dhaheri, now 29, last heard this and other Emirati fables at the age of 12 when they were recounted under the stars by his great-uncle in Al Ain.

"He would be one of the three or four remaining elders of our clan and we would go to him and we would sit very simply," he said. "This was before the massive urbanisation, when you could sit outside the house together in the open. These storytelling sessions were one of the few methods of entertainment." As with many people near his age, he concedes, certain details of stories have now faded from his mind.

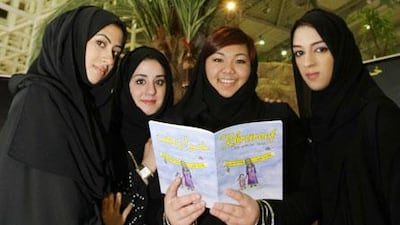

"My memory for some of these things is not so good." But a part of a nation's heritage as vital as its folklore need not become a casualty of modern life, according to a group of Zayed University students. To give new life to the old stories, four communications students have catalogued and published a collection of traditional UAE fairy tales aimed at future generations. The book, Khrareef - "fairy tales" in Emirati dialect - includes a version of the Baba Darya fable, as well as stories about the mirage spirit Khattaf Rafai, the wicked temptress Um al Duwais, the chainmaker Bu Salasel and the poor girl Bdai Bdaiho, who discovers gold and diamonds beneath her pillow.

Without the retelling and sharing of the tales, such cultural treasures could be lost, said one of the students, 21-year-old Raisa al Zarouni. "It seems like no one actually makes the effort any more to tell the stories of before," she said. "Everyone's working now, everyone's busy. Why tell stories when there's television or internet or DVDs to watch? It's a shame." Another member of the group, Atheer bin Shaker, said the students had been motivated to document popular stories when they realised their younger siblings had no knowledge of the traditional characters.

"Our mothers and our grandmothers told us these tales when we were small, but we don't know why it didn't pass on to the next generation," said Ms bin Shaker, 21. "I used to love to hear my late grandmother's stories whenever I slept over in Ras al Khaimah, but it just stopped with us." The group was more dismayed when, out of some 50 children they surveyed between the ages of five and nine, only one young boy had heard one of the five Emirati stories featured in the book.

"When we asked the children about their favourite fairy tales, Cinderella came up, Snow White came up, Peter Pan," said Sarah Ahrari, 21, who also helped compile the anthology. "None of them had even thought of having a favourite Arabic character because they hadn't heard their stories." But more than just telling stories, the students believe Khrareef, of which 600 copies have been printed, offers a valuable snapshot of local life in another era and depicts traditional values.

"One thing that's very predominant in a lot of stories is how so many fairy tales include some elements of the sea," Ms Ahrari pointed out. "Khattaf Rafai, for instance, is an illusion that would show people gold or diamonds or anything they desire, but once the fishermen would follow, he would get farther away until the boat became lost at sea." Like her peers, Ms Ahrari had never heard of the sea myth until the students began the Khrareef project and interviewed a local historian. The cautionary tale about the perils of greed is now her favourite in the collection, which features illustrations by Dina Khorchid, a Palestinian artist who lives in the capital.

Ms Khorchid, 22, spent 15 years in the Emirates and heard the stories of Um al Duwais through her local friends. She learned about the Khrareef project via a group on the social networking website Facebook, and offered her talents. "Even though I've lived here for a long time, I wasn't aware of the traditional stories," she said. "I wasn't sure if anyone had documented these before, so I was very interested because this is also new for me."

The students are well aware that Khrareef is not the first anthology of UAE folklore published in English and Arabic. For last year's Abu Dhabi International Book Fair, Adach printed 1,000 hardcover copies of A Key to Another World, a collection of Emirati stories translated by the Polish journalist Iwona Drozd. But Ms bin Shaker believes Khrareef is the first collection of fables to target young children.

"A lot of the stories are a little bit dark, so we tweaked them a bit in our versions," she said. For example, the seductive Um al Duwais is traditionally depicted as a devious djinn, or spirit, who lures unwitting men to commit adultery before beheading them with a blade she uses for a hand. In the children's version, she retains her captivating beauty and Arabic perfume but tricks children into following her with promises of sweets. She then confronts them with her true, hideous face and the victims are never heard from again.

"That character used to scare us a lot as children," Ms bin Shaker said. "But there was a moral, which was not to talk to strangers." The fear of Um al Duwais still resonates with some elders today, as the fourth group member, Abeer al Ali, learned during interviews with her family members. "When I went to talk to my auntie, she said, 'No, don't talk about these stories. It's real. She's evil, Um al Duwais exists.' I said, 'OK, OK,'" said Ms al Ali, 24.

For his part, Dr al Dhaheri never believed the fairy tales, but he remembers the lessons they were built upon to keep children from wandering out in the summers. "At times, our grandparents would say, 'Don't go out. Um al Duwais is out now.' And nothing would deny us from going out except such stories," he said. "Those of us if we were mischievous, would say, 'Where's Um al Duwais? Come out!' And if we never found her, there was the heat and that would give us heat stroke."

Descriptions of Um al Duwais also vary. Dr al Dhaheri recalls one story in which she is a vengeful spirit who lost her husband long ago. "Um al Duwais is different in Al Ain from that of Abu Dhabi; it's different from that of Dubai and Sharjah," he said. "Each village might have a slightly different manifestation of the character." As a young boy, he heard one of her hands was a sickle. During interviews, the hand was described to Ms bin Shaker as a saw.

"People said to us, 'Um al Duwais should have long black hair, she must be combing it, she has lots of jewellery'," she said. "But they all agreed she was beautiful and had the scent of Arabic perfume." Eman Mohammed, who works at Adach and studied Emirati folklore, said the legend of Um al Duwais frightened many children where she grew up in Ajman. "We heard she cuts off the heads of young men," said Ms Mohammed, now in her 30s. "Later, I used these kind of horror stories for my younger brothers as a kind of protection."

Then there was the nasty Hmar al Qyla - or "afternoon donkey" - a well-known spectre that would chase children if they wandered into the desert alone. "When we were kids," Ms Mohammed explained, "the parents would nap in the afternoon. We of course wanted to play and go out. Because of the heat and the sun, they invented this character and told us, 'If you get out, this character will come after you.'"

As with dozens of other stories, Hmar al Qyla was left out of Khrareef to make room for more popular folk tales, the students said. Dr al Dhaheri has offered funding from Adach should the group decide to collect more stories for a future expanded edition of the anthology. "I'm very proud of this project. This is just a very small collection of tales - there must be hundreds," he said, adding that a collection of Emirati proverbs is another idea.

Ms bin Shaker said the students intended to copyright their book and archive it in national libraries. "When people say we should revive Emirati culture, they will talk about the dancing, they will talk about the music, they might talk about food, but nobody really went to the stories that we all grew up on," she said. "I hope this book shows they're full of morals, they're full of lessons and they're also fun for children."

mkwong@thenational.ae