No matter where you find yourself in the world, the older generation never hesitates to offer advice to the younger generation: “Thank your lucky stars you weren’t born in my day. Life was hard back then.”

In the UAE, this rings truer than in most other parts of the world.

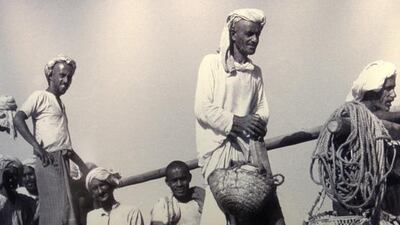

Consider the 1940s. The Gulf pearling industry that had supplied some of the world’s most precious and beautiful pearls to royalty and wealthy families for hundreds of years, was no more because, in 1928, the Japanese perfected the cultured pearl.

The collapse was dramatic and impactful – from 80,000 men on thousands of pearling ships in the early 20th century to a few dozen ships lingering throughout the 1930s and 40s. Men who had supported families along the Trucial Coast suddenly had no income to survive in a harsh physical environment.

According to Sheikha Jassim Al Suwaidi, the first female Emirati photographer, famine stalked the land. Many people, already struggling with the lack of food and money, migrated to Kuwait or Bahrain to avoid starvation. Poor parents offered their children to the care of richer families as they couldn’t support them. And yet life went on – the British explorer, Wilfred Thesiger, noted in the 1940s that despite their hardships, people still “valued leisure and courtesy and conversation”.

What skills, traits and attitudes helped people get through those terrible years? Grit, courage, resilience, persistence, interdependence, boldness, faith and confidence.

So when oil was discovered in the 1950s and life began to change irrevocably from the 1980s onwards, the old skills and attitudes exhibited by the people who survived those very difficult years appeared to dissipate as the ease and comforts of modern life were increasingly embraced.

Sometime in the 1990s, a watershed moment occurred when society’s expectations about life, its sense of meaning and purpose, and the relative significance of the past, present and future, began to shift dramatically.

In the middle of that decade, I arrived from New Zealand to begin a teaching position at a federal university.

Greeting my first class of young adult male Emiratis, mostly recent school-leavers, I noticed a number of things. First, they were all proudly dressed in their kanduras with almost all wearing the full Arabic headdress consisting of the ghutra and the agal. Second, they were shy, quiet and respectful, perhaps because of their poor English and passivity. The latter was maybe a result of their school experiences with overstrict teachers, and a traditional upbringing style based upon the “children-should-be-seen-and-not-heard” philosophy.

On that first day, many clearly didn’t want to be there. They left within the first month in droves, heading to the relative ease and security of public-sector jobs.

Those who graduated changed into much tougher and more competent versions of their original shy and unconfident selves.

Over the years, I began to note the speed and chaos of societal change, during which people appeared to lack the same skills that had strengthened their grandparents’ generation. I noticed their struggle to make sense out of their ever-changing and confusing lives.

Two true, but contrasting, stories are worth telling (with names changed).They illustrate the variation of skills attainment and deployment in modern youth.

Ahmed, the oldest in a family wrecked by divorce, had lost the respect of his mother who had chosen to bestow the “eldest son” role on her second-born. He naturally rebelled against this and was troublesome at college.

I responded by granting him study independence that allowed him to miss most of the classroom assessments in favour of producing a project summarising the key ideas of the course using PowerPoint.

At the end of his final term, he felt very proud of himself. And he relished the accolades he received from his new business diploma teachers when they viewed his 102-slide project presentation.

Every year after graduation, Ahmed came to visit me, still beaming at his success that had at first appeared so fragile.

Next, I thought Jassim, a friendly student with minimal English skills, was going to be one of our successes. He was attentive in class. But within a few weeks, he left to join the police force. He told me he wanted to buy a new car and get married.

Today’s youth do not face famine or starvation. But they do face an uncertain future in a society that has radically changed over the past 20 years. Like most young people around the world, they are searching for a sense of purpose in their lives. Anxious about securing a job and desperate to acquire a sense of self-worth, they wander between staying at home, getting a government job or risking all by applying for positions in the private sector.

What is needed now? Grit, courage, resilience, persistence, interdependence, boldness, faith and confidence.

Dr Peter J Hatherley-Greene is director of learning at Emarise in Dubai