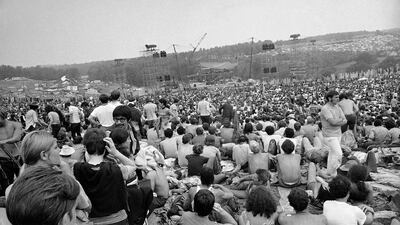

Looking back at what happened exactly half a century ago, in a few fields owned by a New York farmer called Max Yasgur, it might seem remarkable we remember it at all.

As a music festival, Woodstock was a bit of a disaster. First came the world's biggest traffic jam. The crowd of about 400,000 utterly overwhelmed the event, which took place near the small town of Bethel and actually took its name from Woodstock Ventures, the production company behind it.

It rained. A lot. The site turned into a mud bath. Then the food and water began to run out.

What was billed as "three days of peace and music" became four as the festival's timetable fell to pieces. By the time Jimi Hendrix brought the house down with his version of The Star Spangled Banner, it was 8am the day after the event and 90 per cent of the audience had long gone home for a bath and a hot meal.

Yet Woodstock somehow came to symbolise the hope of a better world. The singer Joni Mitchell (who actually sat the whole thing out after deciding a slot on the Dick Cavett Show was a better option) wrote a hit song that embraced those ideals.

In her song Woodstock, she dreamed she saw the "bomber death planes riding shotgun in the sky, turning into butterflies above our nation". Later she described how "the deprivation of not being able to go provided me with an intense angle on Woodstock...[it] impressed me as being a modern miracle, like a modern-day fishes-and-loaves story".

The festival took place at a time when the Vietnam War was at its height. The bombers were in the skies but thousands of American boys and tens of thousands of innocent civilians were dying on the ground.

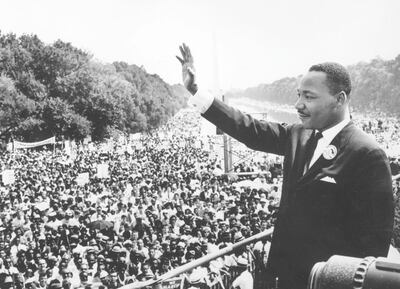

The civil rights movement was fighting on the home front. In the deep south, US cops were attacking protesters with dogs and truncheons and black churches were burning. Martin Luther King had been shot dead the previous year, along with Robert Kennedy, who was running for president as the Democrat candidate. It was Richard Nixon – Tricky Dicky, as the hippies called him – who became president and we all know how that ended.

Woodstock was a political and social statement as much as a music festival. It was a historical marker, a rallying point for a generation as they broke free from the norms and conventions of their parents.

Looking back in August 2019, it also looks increasingly like a bit of a historical curiosity, and not just because of the long hair and flared denim. There is revolution in the air today, but it comes from the opposite direction.

This is the age of populism rather than the Age of Aquarius. Dissent comes from the grass roots but it is insular and isolationist. It fears the other, the outsider, even if they are weak and vulnerable.

It is the Age of Trump, where elected politicians are told to “go back” to their home countries, even though they are American citizens. Across Europe, politicians from the far right such as Hungary’s Viktor Orban find increasing support from ordinary people frustrated by the status quo that seems to have brought them little benefit. Britain also turns inwards in a bitter Brexit debate that has torn a nation in two. For an alternative underground press, we now have internet forums like 8Chan, peddling the kind of race hatred that allegedly inspired the gunman in El Paso to murder.

The slogans of our age are no longer “make love not war” but “fake news” and “send them home”. If anger is directed anywhere, it is at the Woodstock generation, or at least their children, whose counterculture values seem in part to have provoked this reaction but also failed to challenge it.

In this inversion of 1960s values, to be anti-establishment means to become a “disrupter”, a form of political engagement that seeks to pull down existing institutions with vision that seems more nihilistic than idealistic. We are told to “take back control”. But to what end?

In this context, Woodstock seems increasingly nothing more than a curiosity; an exercise for baby boomers who are the only ones now wealthy enough to buy its latest incarnation, an $800 boxed set of 37 CDs that include every artist and every song.

There have been attempts in the years since to recreate its spirit, with little success. Woodstock '99, produced by MTV, descended into a shambles of capitalism. And while there was a concert held on the same spot this weekend, an attempt to put on an official event to mark the 50th anniversary collapsed in a flurry of lawsuits when the money ran out. Rather than progressing forward, the spirit of the Sixties seems to be spooling back to the 1930s.

Before we consign Woodstock to the history books, it is worth remembering that it represents a period when positive social change seemed necessary, whatever the cost.

It has a distorted echo in the slogans of the populist right but can also be seen in the rise of the ecological movement today, even in the disruption of Extinction Rebellion, an organisation with a name straight out of the Sixties.

Woodstock is also a reminder that history moves in cycles. Old hippies never die, they used to say, they simply fade away. But ideas are made of sterner stuff.

The age of Trump and Orban will pass. Brexit will become a distant memory. To everything, turn turn turn, as The Byrds once sang. There is a season and time to every purpose under heaven.