Embroidery. It's been spotted everywhere from the hallowed haute couture runways of Paris to Dolce & Gabbana's ultra-exclusive Alta Moda show in Lake Como. It's why Rihanna's Maison Margiela creation at the Met Gala and Sonam Kapoor's Ralph & Russo outfit at Cannes turned heads and got fashion editors talking. And it's what can make a piece of fabric command hundreds of thousands of dirhams. The age-old craft may sound like a simple case of taking a needle and thread to cloth, but the sheer intricacy it demands in its purest form – hand embroidery – continues to keep it relevant and in demand.

"A hand-embroidered piece tells a story with each stitch that is created. It is a labour of love of that particular embroiderer, a slow process that involves many hours of work, which is so valuable because of the craftsmanship," says Ola Dajani, the Dubai textile and fabric artist who will oversee Needle & Thread, an embroidery workshop at Warehouse 421 in Abu Dhabi on Sunday.

The first known evidence of humankind’s desire to embroider – in the form of fossilised remains of heavily hand-stitched apparel – hails from the Cro-Magnon era, circa 30,000BC. Other early examples include shells stitched onto animal hides in Siberia; pictures rendered in chain stitches using silk threads in China; quilted clothing, tents and armour in Ancient Egypt, India, Persia and Greece; sashiko or functional embroidery to reinforce old clothes in Japan; floral whitework in Ireland; and surface embroidery using rayon in Brazil. The types of stitches, fabrics, pictorial representations and decorative elements – from beads and pearls to silk and sequins – differ widely from region to region, as people used what was available to them, as well as applied their creative faculties to make their handiwork more attractive and functional.

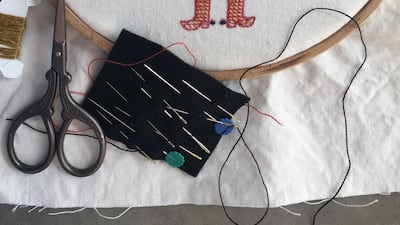

This is also what Dajani hopes to impart in her workshop. The three-hour session will cover the basics of contemporary embroidery, and participants will be taught how to use embroidery hoops and threads of various textures, sizes and colours to create a sampler of stitches. "Those stitches will form the building blocks for any future embroidery work, which the participants can embark upon after," says Dajani. In addition to demonstrating various techniques, the designer will also shed light on the uniqueness of a hand-embroidered piece and the long journey behind it.

“Embroidery, for me, is [more than] just for garnishing or adornment; it’s a part of the design,” says Syrian couturier Rami Al Ali. “Most of my embroidery is created to achieve more texture and three-dimensional proportions for the design, to give it more depth. Each season I try to use an unexpected material that I haven’t used before, to get interesting results out of it. Embroidery is beautiful and timeless; it is something that you can pass on to the next generation, just like art and jewellery,” he adds.

In a sense, this is an evergreen craft that may not have changed much from its most basic form over millennia, but that we continue to create and covet. In fact, embroidery is increasingly being employed as a symbol of empowerment, with many ateliers hiring crafts people from impoverished or politically unstable regions, such as Palestine; or from areas with a rich history of the craft, such as Lesage and Montex in France where the embroidery wing of the house of Chanel operates.

Japanese obi and kimono designer Yamamoto Maki, meanwhile, works with Inash al Usra in Ramallah. The non-profit organisation is dedicated to imparting vocational training in hand embroidery to local women, making them more financially able. Palestinian embroidery is one of the last vestiges of the region’s identity and rich culture. This is also being explored in Labour of Love: New Approaches to Palestinian Embroidery, an exhibition ongoing until August 25 at the museum in Birzeit.

Another exhibition on until September, It All Comes Back to Thread at the Nelson textile museum in New Zealand, displays 50 works that pay homage to the creativity of embroiderers through the ages. Religious rhymes and grand old buildings sit alongside finely detailed flowers and even one embroidery artist’s interpretation of a human skull.

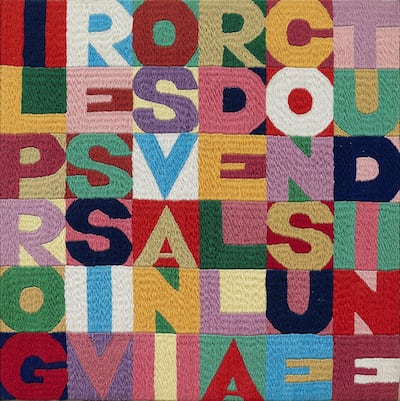

"The reason why many fashion retrospectives draw thousands of footfalls, or why textile collections of museums are so remarkable is because needlework, especially when rendered by hand, is considered timeless," notes Bollywood stylist Anisha Pillai. "It's what makes vintage clothing so sought after, too, especially if the outfits have retained their stitches and beadwork." The same goes for embroidery on canvas, such as Italian conceptual artist Alighiero Boetti's The progressive Disappearance of Habit, which sold at a Sotheby's auction for Dh245,000.

However, when it comes to hand embroidery, a long-lasting stitch rarely ever adheres to parameters of precision. That, though, is the real beauty of such work. “I am not a fan of machine embroidery, to be honest,” says Dajani. “I feel the imperfections of hand embroidery add to the charm. In a world where everyone is seeking perfection, one tends to value manual work. Hand-embroidered garments might look uneven or asymmetrical, but this adds to its uniqueness and should not be viewed as flaws.”

Justin Hoehn of Lead Apparel, which provides brands with hand-embroidered artworks and logos, couldn’t agree more. “Think about it this way: when you customise a product, any product, whether it’s clothing, jewellery, a car… it becomes personal and therefore more important to the buyer. Hand embroidery, too, is such a tool. It’s special and really elevates a product. You can notice the difference in the details in a hand-made piece; I appreciate that hand embroidery isn’t perfect, but that doesn’t denote the quality. Rather, it makes it higher in quality in most cases.”

There are certain things to keep in mind before you invest in such a piece, though. “Firstly, one should clarify whether the garment is hand- or machine-embroidered. It is usually easy to spot the difference, especially when looking at the back of the garment. The back of machine- embroidered garments looks extremely neat, and this is not a case for hand-embroidered items. Garments with hand-embroidery should not be pressed with an iron as this might damage or flatten the threads, I usually dry-clean all my pieces,” explains Dajani.

Hoehn says: “Add embroidery in places on a garment you wouldn’t normally think of, say the inside of the neck, or near the front hem or on the lower stomach area. Use quality threads; they cost only a little more, but last twice as long; and bold colours – the natural sheen of the thread will make them pop.”

Al Ali, meanwhile, cautions about post-care. “Such pieces are very delicate, and difficult to store and keep clean. So always be careful and try to avoid water, humidity and light to keep the metalwork from changing colour,” he advises. The couturier is also a big believer in the subjective value of what he considers an art form. “I think embroidery is like art; what I would like, you probably won’t and vice versa. There are no particular rules in embroidery. Just try as much as you can to buy something that is timeless to enjoy it for as long as possible.”

The Needle & Thread workshop by Ola Dajani will take place on Sunday at Warehouse 421, Abu Dhabi, from 6.30pm to 9.30pm, for Dh150 per person; www.warehouse421.ae/summer-club

____________________

Read more:

10 looks from Dolce & Gabbana's Lake Como-inspired Alta Moda show - in pictures

10 summer holiday essentials for men - in pictures

Sustainable fashion: Ferragamo's new eco-friendly shoe

____________________