Egypt needs to change the storyline if it wants to bring back international tourists to match the glory days before the 2011 uprising. One way would be to foster the wonderful romance of Egyptology, which seems to have receded into the background, to counter the constant news flow of political instability and acts of terrorism.

The obvious game-changer could be the mysterious room thought to lie behind King Tut’s tomb in the Valley of the Kings. If it turns out to be the burial chamber of Queen Nefertiti, the world would be electrified.

But there are plenty of other fantastic Pharaonic sites waiting to be developed. Luxor has been largely immune from the instability in other parts of Egypt, and small amounts of cash directed towards high-visibility projects, preferably channelled privately and without conditions, could also help. Tourism revenue collapsed to $6.1 billion in 2015 from $12.5 billion in 2010. In February of this year, the number of visiting tourists plunged to almost half of what it was a year earlier, mainly the result of the bombing over Sinai of a Russian airplane in October. The outlook for the rest of 2016 looks equally dismal.

One potential tourist site, which I visited recently, is a stunning canal built by Amenhotep III (1387-1348 BC) from the Nile to his palace on the West Bank at Luxor. The amount of earth moved to dig it is said to match that of the great pyramid. Amenhotep, one of the ancient Egypt’s most powerful rulers, also gained fame as the father of the heretical Pharaoh Akhnaten. Why not develop that as a site and open it to the public with suitable fanfare?

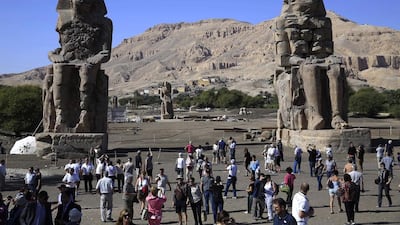

The site with the most potential in my mind, however, is the temple of the same Amenhotep, which also lies on the West Bank, smack on the main road to the Valley of the Kings. The site has long been famous for its two massive statues, the Colossi of Memnon, which stand on either side of what was once the temple’s main gateway, but was otherwise ignored until the Egyptologist Hourig Sourouzian began working at the site in 1998.

An earthquake severely damaged the temple 150 years after Amenhotep died, and his successors began using its stones to build other monuments. Another earthquake in 27 A.D. caused more damage. Over the millennia, the site was covered with a 2.5 to 3.0 metre layer of sediment above the original temple floor. Because the earthquakes knocked over the statues, the sediment protected the statues over the centuries, with some bits still retaining glorious detail. What one sees from the road is only a fraction of the original temple grounds, which were 550 metres long and 700 metres wide. The grounds extend under the road and into the fields on either side. The antiquities ministry only controls the main axis, which encompasses a mere 10 per cent of the total temple. Under the surrounding farmland probably lie magazines, the treasury, gardens, pools and administrative buildings.

Ms Sourouzian, who has focused on the three main gateways, or pylons, and the huge columned hall, says she has barely scratched the surface in her 18 years working at the temple. She receives private donations through the World Monument Fund and the Association des Amis des Colosses de Memnon.

“There is probably enough work for several generations,” she says.

The Colossi of Memnon, which actually are 21-metre-high statues of Amenhotep himself, were built from single pieces of red quartzite quarried at Gebel Ahmar near Cairo, then placed on pedestals at the temple entrance. One wears the crown of Upper Egypt and the other the crown of Lower Egypt. Each year her team has been slowly excavating the grounds around the first pylon, constantly finding bits of original stone they can refit into their spots in the pedestals. Her team has also been uncovering yet more pieces from earlier excavations.

They started excavating the temple’s second pylon in 2002, digging up and reconstructing new 13.5-metre-high colossi, also of red quartzite, that once stood on either side of the gate. They later used airbags to lift them into place. Major pieces, including the head of the southern statue and the face of the northern statue, are still missing but quite possibly may still be found.

The team recently started excavating the area around the third pylon and is working to reassemble the 13- to 14-metre-high southern statue, a process that means sorting and collating thousands of fragments. They began with the chest and shoulders, and in recent excavations have uncovered the upper and back parts of the head and the beard, plus bits of the leg, hips and hands. They hope to raise the statue this year.

The third pylon’s two statues were made of white alabaster and mounted on black granite blocks, unusual for Pharaonic art. The head alone is three metres high. Four of the pedestal’s inscribed granite blocks were found at the site, some in pieces, and another six were found across the Nile at the temple of Karnak, usurped from Amenhotep’s temple site in antiquity.

Beyond the third pylon lies a huge columned hall that covered an area twice that of the Luxor temple hall across the river and that rose as high as the massive hypostyle at Karnak. Standing between its columns the hall originally had 38 statues of Amenhotep, each 8.5 metres tall, and probably hundreds of statues of the lion-headed goddess Sekhmet, each carved differently. As an indication of the temple’s vast scale, another gate stands to the north 360 metres across of farm and other land, so far away the connection with the main temple is not immediately apparent. Teams from the Egyptian antiquities ministry and Sourouzian’s project excavated and reconstructed two other colossi statues at the gateway in 2013.

Ms Sourouzian hopes to open the site to the public as an open-air museum within a few years, complete with pathways, stations with explanatory panels and a detailed model of the temple. Too many of the temple’s stones have been pilfered over the last three millennia for it to completely regain its former glory, but enough remains to make a spectacular tourist site — and to keep the romantic side of Egypt in the news.

Patrick Werr has worked as a financial writer in Egypt for 25 years.

business@thenational.ae

Follow The National's Business section on Twitter