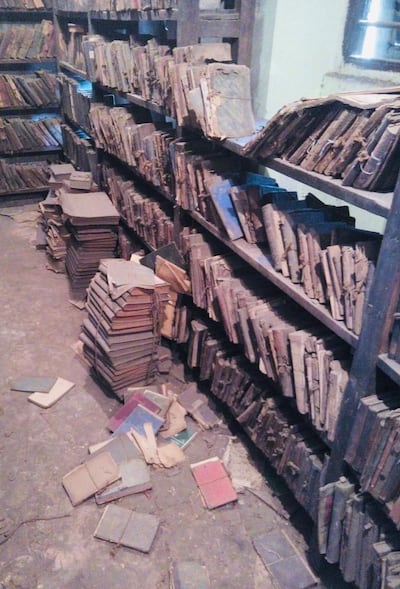

India gained its independence from British colonial rule in 1947. It was a victory for the country in many ways, but as the English left, libraries that were maintained by them fell apart and their collections were sold as scrap paper.

Back then, India had more pressing issues to focus on. More than 75 per cent of its population was living at or below the poverty line. Illiteracy levels were high, so libraries and their collections were seen as luxuries. Periodicals and books that weren't recycled, were bought by collectors, who in turn donated or sold them to libraries abroad. A wealth of material was lost, even more was dispersed around the world and eventually forgotten.

Then came Rahul Sagar, a professor of political science at New York University Abu Dhabi, whose interest in the foundations of modern Indian thought led to him discovering a few of these forgotten documents and inspired him to pursue a wider project: Ideas of India (www.ideasofindia.org), an online resource that indexes more than 300,000 rare and historic Indian texts from the 19th century. It is a project that has taken him and his team five years to accomplish.

"It all began in 2013, while I was teaching a class on the history of Indian politics at Princeton," Sagar explains. "I sent my syllabus to a colleague, who took a look at it and advised me to teach works besides those of well-known figures. He told me I shouldn't just recount a well-known story. There were other stories to tell."

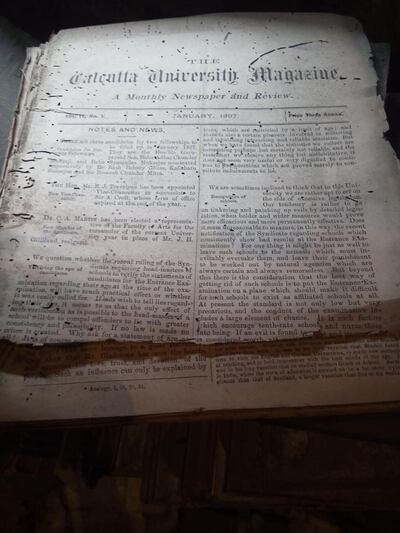

Sagar took his colleague's advice and dived into the archives at Princeton. There, he found three periodicals written in English by Indian authors in the late 19th century. These served as the forum where statesmen and intellectuals formulated and debated the ideas that have shaped modern India. "They are beautifully written," Sagar says. "Essays on caste, gender, science and travel. I immediately called up some colleagues. No one knew the essays even existed."

He noticed that some of the articles were direct replies to ideas published in other periodicals. The realisation took the professor down a paper trail that ran the world over, from New York to Singapore and Australia to India. Aided by research grants from the US, Singapore, and NYU Abu Dhabi, Sagar employed research assistants around the world to collect and index the contents of these articles, making it significantly easier for scholars to pinpoint which one might be relevant to their research and to trace physical copies. "What started out with three periodicals, became 16 then became 26," Sagar says. "I realised then … gosh, I'm up to something.

I decided I was going to make this map. My tribute to the country where I was born."

Crowdsourcing India’s modern history

The work was immense, but the timing couldn't be more perfect. Thanks to instant messaging apps such as WhatsApp, high-definition mobile camera and cloud storage, the project became a more practicable task. "I would've given up and moved on to something else," he admits.

Instead, he says: “I recruited 150 research assistants, I trained them to use their mobile phones to take scans the right way, with the right amount of lighting. I taught them how to look for these journals, where to find them.”

The end result was a synergy of worldwide grace. A research assistant would find a text in New York or in London in the morning, and by the end of the day in Singapore or India, a transcriber would have read through it and listed the essays by subject, author and date of publication.

However, it wasn't an easy task. The professor and his team were piecing things together, bit by bit. Some leads were unproductive. Sometimes catalogued documents were lost. If one volume was found in the United States, it's follow-up could have been in New Zealand or Canada, or anywhere in between.

“And some libraries didn’t have catalogues at all,” Sagar says. “In India, we had to sift through library materials, thumbing through documents, hoping to find something. We kept a spreadsheet of the index, and it was an absolute delight to watch it slowly filling up day by day. You could see it growing in real-time. It was a beautiful thing to witness.”

Crossing the black waters

The works also contained essays by the first Indians who went abroad.

"We have the first pieces of poetry written by Indians in English. We found an essay written by the first Indian to travel to Japan and that first encounter with Asian modernity," Sagar says. "We have essays written by the first Indian to enter the British civil service. He writes about what it's like to pass through the Suez Canal. We also have quite a few essays by Indians who travelled to the Gulf, detailing their experiences of interacting with the regional culture."

Sagar is particularly moved by these debates on travelling overseas, or crossing the "kala pani", meaning black waters. To do that would mean losing caste and religious standing.

"Hindus and Muslims at the time believed that travelling overseas was sacrilege," Sagar explains. "The view was if you travelled abroad, you might not follow the rules of your caste or religious order. You might eat meat, accidentally drink impure water or interact with women. Here, we can monitor your actions. There, we have to take your word."

Sagar describes those who journeyed across the kala pani as solitary figures treading against a very old and conservative society, who viewed them as heretics and outcasts. Yet, he says they believed their journey would become beneficial for India's modernisation. "The essays about their journies really tell you something about the power of education, learning and reading. An amazing example of how ideas change the world. I had more goosebumps reading their works, than I ever thought possible in a lifetime."

The rise of periodicals in India

After the English schooling system was introduced to India in 1835, Indian students found that their professors were reading English periodicals and became interested in the medium.

Indians soon embraced the medium, finding it to be an ideal platform to debate and think about politics in a reasonable way.

More than 300 periodicals came into existence between 1857 and 1947. Some lasted only a few years – they had small circulation and were not financially viable.

“But even those smaller papers had an average of 600 official readers, which, in reality meant three to four thousand readers … People shared their copies. Some were put in the library. Each copy was read some 25 times.”

Two dozen of these publications lasted a substantial amount of time and had a great impact. Three of the most famous ones were: The Hindustan Review, Modern Review, and Indian Review.

“Those three were the ones I first found,” Sagar says. “Some of the essays were written by the most famous people of the day, yet almost no one knew of their existence. The essays were posing some really interesting questions. Questions about reconciling traditional values with the changes of a modern world. Questions still being asked around the world.”

What’s next?

The index allows researches and amateur historians to find these texts by searching for subject, name of the journal page numbers.

"Now what I'd like to do is digitise the periodicals." However, to do that, Sagar and his team will need funding. "It will take around two to three million dollars for it to happen," he says. "The money is to pay the libraries for the right to copy the information. The contents are not copyrighted, but they belong to the library. It's important they get their due, because they worked to preserve the documents."

Sagar says he could approach a publishing company today and get the funding. “But then it won’t be free for universities and amateur historians to use. My aim is to make the index and digital archive accessible to everyone.”