A museum immures artworks against the decay of time: mummifying them in vitrines, controlling the temperature and humidity to prolong an artefact's life. But it's no use pretending that time doesn't advance. We, the viewers of art, grow old; civilisations march forward (and backwards); the light moves around us.

Louvre Abu Dhabi's first contemporary art exhibition, produced in partnership with leading French manufacturers, is devoted to the eternal subject of time itself. Curated by Alia Zaal Lootah, Co-Lab: Contemporary Art and Savoir Faire opened in December and closes on March 25, so there are only three weeks left to see it. It comprises four discrete works that are themselves products of time: indices of two-year collaborations that hold within them stories of co-operation, changed plans, intense research, and the latent symbolism of artists and designers from the new country of the UAE working with the august knowledge of French artisans.

The following are some of these stories, about the work by the UAE-based artists and designers Vikram Divecha, Talin Hazbar, Zeinab Alhashemi and Khalid Shafar.

Monet the timekeeper

For his video and sculpture Train to Rouen (2017), Divecha looks back to how time was first standardised, in the late 19th century, in response to the advent of the railway system. As is typical for the Dubai-based artist, the project involves several partners, an inversion of typical events, and a fascinating back story.

Before railways, Divecha says, “every town in France had its own solar clock. They would have two clocks outside every railway station – one had the local time, one had the railway time”. Needless to say, “this created a lot of confusion for the railways. People would miss trains, there would be accidents”.

In 1891, France adopted Paris Mean Time as the country’s national standard time – but Divecha adds that the railways also adopted, in the same year, “a five-minute delay for non-punctual passengers”.

"I began thinking, on one hand, about how they were trying to structure and organise time," Divecha says. "But still there was this levier that was included within the system. It wasn't completely made concrete. There was flexibility in there. I still have five more minutes for my train. I can keep puffing my cigarette, I can keep gossiping with my friends."

The train delay went on till 1901, when France adopted Greenwich Mean Time. Divecha had this delay in mind when he came across a story about Claude Monet wanting to delay a train to Rouen by half an hour in order to get the best light for his painting. He considered it in relation to Monet's masterful, famous The Gare Saint- Lazare (1877), which is on loan at Louvre Abu Dhabi. A classic of modernism, the painting's main subject is modernity itself, symbolised by the train.

"I find it really paradoxical that Monet employed his study of light to make a painting that celebrates modernity and the railways – the railways that fractured our relationship with organic light," Divecha says. "I got obsessed with how light moves. I started to think about the dome in the Louvre – and the patterns it makes on the floor – as some sort of solar clock. And I was thinking about Monet as some unknowing timekeeper. His paintings capture a specific time and day, a specific position of the Sun in relation to the Earth." For Train to Rouen, Divecha partnered with the embroidery company MTX, whose directer of development, Mathieu Bassee, became his "partner in crime", profoundly engaging with the project. Together, they recreated France's erstwhile five-minute delay, partially fulfilling Monet's wish – on October 4, 2017, the 12.19pm train to Rouen left the Gare St Lazare at 12.24pm.

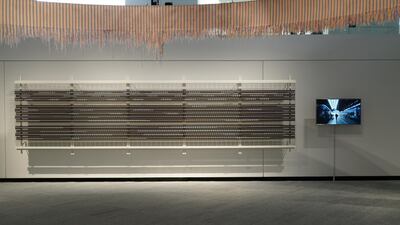

Divecha's work is both a video showing the train waiting for five minutes, and a wall-based sculpture based on the 24-hour timetable French stationmasters use. The artwork, a grid – reminiscent of the roof in Monet's painting – separates time into minutes, while grey-and-white ribbons running through it represent, respectively, the time trains were supposed to leave and the time they actually left.

The project pits two understandings of time against each other. “The system divides time into minutes, but the ribbons run through them in a very fluid way,” Divecha says. “Formally, the works integrate this idea of time as something that’s moving and organic, versus time that’s rigid and static.”

This echoes the Monet painting. “Once steam comes out of the train, it becomes amazing and fluid and blurs out the roof grid – which is an emblem of modernism. It’s these tensions in the painting which we’re trying to include in this work.”

Deep time

For Hazbar, who made the structures Transient: A Brief Stay (2017), the question of time stretched back farther, into the archaeological sites that are dotted around the Emirates, unearthing the forts and domestic sites that stood on the peninsula hundreds of years ago.

Hazbar is fascinated by the inherent properties of material, and how they challenge human desire. The natural entropy of the fine desert sand, for instance, means it cannot retain a shape. Hazbar, who was born in Aleppo and has long been based in Sharjah and Dubai, located some of that potential for chaos in archaeology, where, in uncovering layers of a site, archaeologists must decide at what point they will continue to excavate, and at what point excavation is destroying remnants of what exists.

In a sense, she says, “It’s all very subjective. Who decides what is valuable? There is no right or wrong. Who decides when they are ruining the site, or restoring it? It’s a very fragile layer and each layer tells a lot.”

For the Co-Lab project, she paired with the Manufacture Nationale de Sèvres, whose fine porcelain figurines, like archaeological remains, are likewise attempts to prolong cultural forms. At a certain point, for example, porcelain was deemed a more trustworthy guardian of colour and form than paintings, and in the 18th century, the Sèvres administrator Alexandre Brogniart set about extracting images from major paintings and casting them in porcelain sculptures, keeping these painted masterworks alive by other means. Hazbar used this idea to explore both preservation and cultural exchange, bringing these forms of cultural prolonging into the dialogue with archaeology.

She brought sand from different sites around the UAE to the Sèvres studios, close to Versailles, where the artisans experimented with using sand in various Sèvres shapes from the 18th century. For Hazbar, the sand, which she transported in plastic bags in her checked luggage on the plane, became the "visitor material" being set into the "host material" of the porcelain. When she brought the work back to the UAE, the roles were reversed: she embedded the porcelain forms in sand, which acted as the host material in the series of standing columns she titled Transient.

Accelerated UAE time

In the Emirati artist Alhashemi's Metamorphic (2017), the project became a meeting point between nature and culture, and a way to understand the fast-paced changes of the Emirates.

Alhashemi worked with the glassmakers of Saint Jus in St Etienne, who manufacture traditional stained glass windows and who have collaborated with such artists as Marc Chagall and Henri Matisse.

"I have an interest in how the mind works," she says. "An artisan's mind is passionate about mastering something. And repeating it and repeating it and repeating it. And then making it exactly the same way. But the human touch can never make it like a machine would do, so you are always going to have the flaws – and that's what I love about it."

Alhashemi put together eight panes of glass that relate to the unique colours of the sea of Saadiyat Island, the greenish bright blue of which is different, she says, from the colour of the sea in other emirates. She placed these in vertical supports, and then bound them with the twisted metal that is used to support scaffolding around construction projects – a form of imprinted metal that is quite beautiful when viewed up close.

“You don’t normally see the complexity of the scaffolding,” Alhashemi says. For this work, “the way it was cut and placed in a window reminds me of a moshrabiya, which is more common in this region”.

“I liked the idea that the glass would come back here and the concrete enforced metal mesh would be from here. If you look closer, it even has the initials of the UAE on it.”

Alhashemi explains that the eight-pointed star she has created – arranged into an 2 x 2 metre cube that is suspended from the ceiling – relates to the pace of change of her native country.

“Saadiyat is a natural island, but is seen now as a cultural district,” she says. “I am used to seeing buildings, or manmade lakes, or islands, and wondering whether they’re manmade or not. We are changing the topography – which is not something natural, but we are making it look natural for our own comfort.”

Pitting the two together suggests the co-existence of the subjects: the manmade construction and the natural glass, showing how quickly, and beautifully, an element of nature can be transformed.

A clock with no dial

Shafar, a furniture and product designer who is based in Dubai, wove a tapestry that tells time through colour. It tracks a full year – 365 days – through subtle changing gradations of colour, anchored by a rigorous methodology.

“The process started with a generic question of how we perceive things through time,” he says. “Do we perceive different colours at different times of the day?” It’s a query reminiscent of Monet, which Shafar took in a different direction – he sought to use colour almost as a legend that will show time’s passing through the months and seasons of the year.

He began with an artwork that he had owned for more than 20 years: a wristwatch by the artist Tian Harlan – titled, like Shafar's project, Chromachrone – that told the time by colour. "The dial has no numbers. The amount of colour you see is the time. Yellow," Shafar says, "is for noon – the brightest colour in the day."

Shafar used the library of colours at the weaving factory of the Mobilier des Gobelins, de Beauvais et de la Savonnerie, which typically make tapestries and carpets. “We identified 12 colours for 12 hours,” he says. “Each of those 12 colours is repeated twice – for 24 hours. Then we have 12 shades of each colour. That’s how we move through the months.

“The shading moves from the brightest mood in the spring – the full bloom – then going to the summer, and then fading and become whitish and then darker over fall and winter.” Starting with the first day of spring – March 21 – it wends throughout the entire year, finally brightening again as winter turns back to spring.

_______________________

Read more:

Louvre Abu Dhabi launches the world's first roadside gallery

From One Louvre to Another tells the story of the Louvre in Paris

Louvre Abu Dhabi represents cultural understanding through the ages

_______________________

Like Divecha’s project, the work shows the artis nudging against both the rigidity of both standardised time and the specific process he has devised.

Tendrils from the tapestry hang down from the long cloth, which circumscribes the exhibition like an awning. They are reminders, Shafar says, that time doesn’t always stay within a day.

“Some of your actions remain with you forever, like memories that build up,” he says. “We left the end of each day open.”

The Co-Lab works remain in the Louvre Abu Dhabi collection but it is not clear where they will be next exhibited. They're taking their secrets to the museum archive, biding their time until they are on view again.

Co-Lab: Contemporary Art and Savoir Faire runs at Louvre Abu Dhabi until March 25