In the end, it all came down to chance and the blessing of peripheral vision - figuratively and literally.

In 2011, Jessica Morgan, the newly appointed Daskalopoulos Curator at London's Tate Modern, was in the Middle East, hunting for artwork that would help the British institution fulfil its ambition to broaden the geographical scope of its collection.

"We had been moving into collecting in the Middle Eastern region and she'd been doing a lot of work there," recalls Ann Coxon, one of Morgan's fellow curators. "She was in Beirut, visiting Saleh Barakat, one of the dealers, and he was showing her work by young emerging contemporary artists when she spotted something out of the corner of her eye, and said: 'What's that amazing thing?'"

That amazing thing was Poem, a sculpture created in the mid-1960s by an artist who was now neither young nor emerging - Saloua Raouda Choucair, well enough known in her native Beirut but, until that moment, virtually unknown in the West.

Morgan's chance find would change all that. Delving further into Choucair's story, she discovered a fascinating tale of an Arab artist who, embarking on a journey of exploration of western abstraction in the 1950s, had not only been ahead of her time but also, through her application of the concept of Islamic aesthetics, had built a pioneering creative bridge between two cultures.

The Tate acted immediately. In 2011 and 2012, supported by contributions from members of its Middle East-North Africa acquisitions committee, it bought three pieces by the now nonagenarian artist: one oil painting, Composition in Blue Module (1947-51), and two sculptures: Infinite Structure (1963-5) and Poem of Nine Verses (1966-8).

Three more sculptures were donated, two anonymously - Poem (1963-5) and Poem Wall (1963-6) - and one, The Screw (1975-7), was presented by the Saloua Raouda Choucair Foundation, managed by the artist's daughter.

Five of those six pieces can be seen currently in Structure and Clarity, a themed section of the Tate Modern's permanent exhibition, on level four of its imposing building on the south bank of the River Thames. There, as part of a theme that explores the development of abstract art since the early 20th century, Choucair has found her place in art history, alongside the likes of René Magritte, Pablo Picasso, Piet Mondrian and Henri Matisse.

And, if that sounds like a fairy-tale ending for a still-living artist who spent her working life in relative international obscurity, it will be topped next month when the Tate stages the world's first major museum exhibition of Choucair's work, bringing together 120 pieces from a six-decade career, many of which have never left the artist's home, let alone been shown in public before.

"It is so unusual to encounter an entire oeuvre of such an important figure," says Morgan. "It's a great honour to be able to present the work at Tate."

But within this triumph of vindication lies tragedy. Now in her 97th year, Saloua Raouda Choucair has been robbed by Alzheimer's disease of the ability to fully appreciate her long-overdue recognition.

"It is very tragic," says the Tate's Coxon, who is co-curating the Choucair retrospective with Morgan, "especially for her daughter, who is now trying to piece together and be a spokesperson for what her mother was thinking, now that curators have come knocking at her door." The difficulty of the task for Hala Schoukair - her name differs slightly from her mother's thanks to an accident of passport-office bureaucracy - is compounded by a sad fact of life familiar to many families.

"The interest in her mother's work," says Coxon, "and in trying to archive it, catalogue it and speak for it has probably come slightly too late, in the sense that when her mother was more compos mentis they weren't having the conversations." In recent years Hala has been a tireless campaigner for her mother's art, curating a retrospective of her work at the Beirut Exhibition Center in 2011 and hoping to find a home in Beirut for a permanent exhibition.

The Tate recognition, she says, is "very rewarding and important, definitely, but now my mother lives in her own world. She is almost 97, very frail and losing her vocabulary. She can't find her words."

For a moment, neither can Hala.

Her mother, she says, "had a tough career, she was ignored". She won a prize at the 1968 Alexandria Biennale "and it was barely mentioned in the press. If any other Lebanese had won a prize like that they would have written articles about them, but they just didn't want to give her the importance she deserved."

Her mother will not be able to travel to London for her exhibition, which opens on April 17 and will run for six months.

"She went to the show that I made for her in 2011 and she was very happy to see it and when she grasps what's going on she is really happy. When the Tate took pieces into the permanent collection she knew this had happened and she was very pleased, but this year she has had a little plunge and is very frail."

Choucair was born in Beirut in 1916. The Tate credits her with being Lebanon's first abstract artist and says her 1947 exhibition at the Arab Cultural Gallery in Beirut is considered to have been the first exhibition of abstract art anywhere in the Arab world.

Given the artist's later fascination with the mathematical complexities of Islamic art, it is perhaps unsurprising that her journey began in science, as a biology student at the American Junior College for Women, which later became the Lebanese American University. For Choucair, art and science were travelling side by side. By the time she graduated with her biology degree in 1936, she was already studying with the Lebanese landscape and portrait artists Mustafa Farroukh and Omar Onsi, but in 1948 she moved to Paris to study at L'Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts. There, and especially while working in the studio of Fernand Leger, she became exposed to European modernism.

It inspired her, says Coxon, but she was already developing her own ideas as an artist.

"She had already started to experiment with abstract compositions, this idea of using mathematical formulae to make geometric abstract designs, and she was obviously inspired by Islamic art and had already developed this belief that the Arabs had in some way got things right."

In pre-war Beirut, the fashion in art was heavily influenced by western realism and impressionism, but Choucair - "perhaps instinctively", says Coxon - had other ideas.

"She was led towards the abstract and a belief that actually the Arabs may have been on to something years and years before the western modernist canon had picked up on abstract forms of representation."

In Paris, she became involved with and influenced by the Atelier d'Art Abstract, a collaborative group of artists committed to the concept of non-representational abstract painting, but it was only after she returned to Beirut in 1951 that Choucair found her own path.

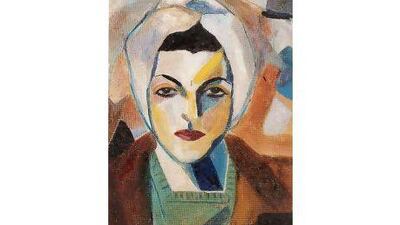

The various influences to which she was exposed can be seen in her early work, all of it paintings, frequently derivative, and the visual diary of an artist feeling her way towards her own style. The most striking is Self Portrait, painted in 1943 - and so striking that the exhibition's curators, after admitting they wrestled with the conscience of their curatorial integrity, chose to use it as the poster image for the Choucair exhibition, despite it being so uncharacteristic of her work.

It is not by chance, however, that sculptures will form the bulk of the Tate's Choucair retrospective and that only one canvas has made it into the museum's permanent collection. Composition in Blue Module, executed between 1947 and 1951, while Choucair was in Paris, is a halfway house, hinting at the geometric designs through which the artist would find her ultimate expression. It was in sculpture, says Coxon, that Choucair found "a unique way of translating ideas that come from a kind of hybrid of western modernism and Arab tradition".

Modular pieces such as Poem and Infinite Structure are designed to echo the format of Arabic poetry, in which each stanza may be read alone or as part of the whole. But they are also inspired by something far more fundamental to Islamic tradition, in which, says Hala, the seeds of abstraction may be found.

"In Islam, God has no adjective; you cannot describe Him - it is an abstract philosophy and this was how she was thinking. The Arab artist, when he wanted to express God he made infinities of arcades where you cannot see the end - the idea of infinity is the representation."

Likewise, she says, her mother was taken by the idea that Arabic itself was, in a sense, an abstract language and from this concept came the translation of the construction of Arab-Islamic poetry into sculptural, modular form: "They are built, in a way, to go to infinity; they don't end; you can add forever, one piece after another." Her mother, she says, was driven by respect for communication and what she saw as the perpetual creative dialogue between East and West.

"She wanted to have an impact, to show that the Arab world could be modern. If you think of the Renaissance, it took a lot from the Islamic world and now we are taking science and philosophy from the West - there is dialogue. My mother never saw a divide, she always thought of it as the same circle, that comes and goes." For the Tate, Choucair's significance lies in how her ideas "relate to art we know or are more familiar with in the western world", says Coxon. "Coming from her they have a different way of looking at things, inspired by Arab traditions, so it's a reconsidering of some of the things we think we know about modular sculpture."

For Hala, who still hopes to find a home in Beirut for a permanent exhibition of her mother's work, the Tate show represents an opportunity for her mother to fulfil her destiny - and, in a sense, for Islamic art to claim its rightful place in an international canon.

"She was always trying to be part of the modernisation of Arab society," she says. It was such a long frustration for everybody - for every intellectual who wanted to take the society into the modern world.

"I lived with her frustrations, so this is a relief for me. This is a milestone in my life … she is getting the reward she should have had."

Ÿ The Saloua Raouda Choucair exhibition runs at the Tate Modern in London from April 17-October 20

Jonathan Gornall is a regular contributor to The Review.