A largely ignored childcare crisis forms part of a "vicious cycle" of poverty in rural America, the chief executive of Save the Children US says.

Many European countries such as France and Norway provide heavily subsidised or even free child care. In parts of the Middle East, employers are required to provide or support child care for their employees’ children, while in other regional countries, domestic help is available and relatively affordable.

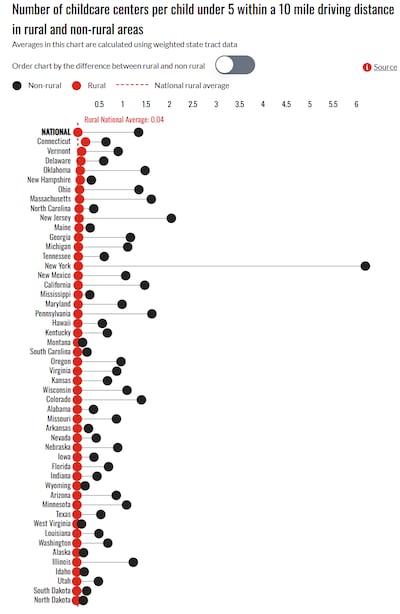

Millions of Americans, meanwhile, are facing a childcare crisis. In many parts of the country, particularly rural areas, child care is either unavailable or too expensive.

“Communities do not have access to appropriate child care, which means it's not good for kids, who lack quality development and care,” Janti Soeripto, chief executive of Save the Children US, told The National. “And it's hard for parents that go out and work, and so on, and so on.”

Rural challenges

The lack of child care in rural communities is inextricably linked to the economic situation in these areas, where about 25 per cent of the American population lives. A lack of jobs and investment, as well as isolation, has contributed to widespread poverty.

Rural America is typically “disproportionately poor and under-resourced”, Ms Soeripto said.

“More people, as a percentage of the population, live in poverty in rural America than in urban or non-rural centres,” she said. “Only 7 per cent of philanthropic funding goes there. I think even less for federal funding.”

When child care is available, access is complicated by distance.

Public transport is nearly non-existent in many parts of the rural US, and many do not have reliable modes of private transport. Family and other support systems are shrinking as more people move away to gain access to better jobs and services.

Karen Thompson, interim executive director of the Appalachian Early Childhood Network, said poverty as well as isolation make confronting problems in rural areas – such as the lack of child care – difficult.

She spoke of the sometimes closed nature of many rural communities, which hinders efforts at contact.

“If they don't know you, then it's an us-and-them situation immediately,” Ms Thompson told The National. “So it's really hard to earn trust, even when we have programmes to help them.”

She said jobs with awkward hours and lack of reliable transport created a cascade of failures for families. “You need child care but you need it close, but if you don't have a job that works those [typical childcare] hours, that's challenging,” Ms Thompson said.

Locals looking to provide childcare services often face challenges such as difficulty recruiting and retaining qualified staff, and dealing with overhead costs.

“We saw most clearly during the pandemic, of course, when all these centres were closed,” Ms Soeripto said. “A lot of them are out of business, because … it's very hard to make them actually work financially, so that it's affordable for families to go there.”

She said that childcare deserts have become a “real problem”. And it is not only rural areas facing these challenges.

Carol Burnett, founder and executive director of the Mississippi Low-Income Child Care Initiative, said high costs and long waiting lists for spots have contributed to a national crisis.

“The nation's public-funded childcare assistance programme, the Child Care and Development Fund, only serves about one in six eligible children and in some states the funding challenge is worsening,” she told The National. “I wouldn't say this is an urban/rural problem. Rather, it's a failure on the part of our nation to invest adequately in early childhood education.”

Filling the gaps

One way advocates hope to address these issues is by trying to fill gaps left by various federal and state-level programmes.

“It's very much a patchwork of federal agencies that deal with issues around rural America,” Ms Soeripto said. “It's so splintered, it is really difficult.”

She added that even when assistance is available, it's often challenging to access it.

“It's very difficult to understand how you get access to it,” Ms Soeripto said. “Then you have to apply for it, there's a lot of paperwork, sometimes conditions and demands to go somewhere in person – how do you do that if you don't have a car?”

Save the Children has joined a bipartisan commission launched by the Brookings Institution and the American Enterprise Institute on rural prosperity. Over the next year, commission members will visit and listen to those involved across rural America, and conduct in-depth analyses to propose policy changes.

“They [rural Americans] don't have lobby groups, they don't have the resources to come up with a political strategy to get political support for it,” Ms Soeripto said. “There has been a huge lack of economic development in those areas because there hasn't been a very deliberate, intentional strategy towards how these areas could be developed.”

A major area of focus for advocacy groups is workforce development in the childcare field, providing training and removing barriers for aspiring early educators.

“We're helping them help folks that want to open childcare opportunities, because we're in a desert,” Ms Thompson said. “And we don't want just child care. We want quality care.”

That means supporting potential childcare workers in getting their certifications and childcare start-ups to help meet the needs of local families and keep them in the area, in addition to generating more jobs.

A long-term lack of attention at the state and local level to childcare needs is beginning to shift, advocates say, but policymaking takes time.

“Despite the increased attention, little movement has occurred to meet the need,” Ms Burnett said. “What is needed is adequate public funding so all eligible families can be served.”