It was always a matter of time. Late last week, the first coronavirus case was discovered in Idlib, a province in Syria bordering Turkey where hundreds of thousands are living in crowded refugee camps after fleeing war. Without urgent measures to contain any potential outbreak, it could spell disaster for one of the most vulnerable communities in the world.

News of the first infection emerged last Thursday, and by Tuesday the number of confirmed cases had risen to four, including two in Idlib and two in opposition areas in rural Aleppo. All, according to the UN’s Office for the Co-ordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), are healthcare workers, which means it is likely that they were in contact with patients who visited their clinics or hospitals. They are all currently in isolation and contact tracing is under way to see who else may be infected.

Aid workers have long warned of the dangers of an outbreak in a place like Idlib and the devastating effects it could have. To understand the risks, we need to take a step back and examine the situation as a whole.

Idlib is one of the last remaining areas outside the Syrian government’s control after nine years of attempted revolution and civil war. It is under the control of armed groups, some of whom used to be affiliated to Al Qaeda but severed ties a few years ago. The province, which is in north-western Syria, is home to about 4.1 million people, including 2.7 million who were displaced during the war and who need humanitarian assistance, and most of whom are women and children.

A ceasefire has been in place in Idlib since March. But before that, the civilian population endured the full brutality of the Syrian government and its allies, from unrelenting air strikes to chemical weapon attacks and the bombing of hospitals, schools and refugee camps. When loyalist soldiers reclaimed parts of Idlib earlier this year, some of them dug up and desecrated bodies of the dead in local cemeteries.

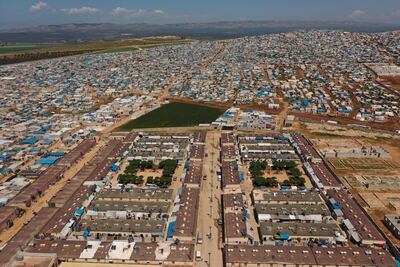

Almost 800,000 people fled the fighting in Idlib between December and March, and the vast majority of them still live in crowded tents near the border because they are too afraid of returning to their homes only for the fighting to erupt again. It is horrifying to contemplate the possibility of an outbreak in one of those camps, with the lack of water and crowded conditions making practices such as social distancing and frequent handwashing and sanitising a pipe dream.

Idlib is also in a poor position to grapple with a public health crisis. The Assad regime has systematically bombed hundreds of healthcare facilities in areas controlled by the opposition, and this has left few hospitals and clinics able to deal with an outbreak. Another seven hospitals have suspended routine operations to limit the spread of the virus in medical facilities.

Instead of making it easier for aid agencies to send medicine and testing kits across the border to arrest the spread of the pandemic in these impoverished areas of Syria, both Russia and China held up the renewal of a UN mandate to deliver cross-border aid, finally agreeing to a last-minute deal that saw the closure of one of the two remaining border crossings through which humanitarian aid flows from Turkey into the rebel-controlled parts of the country.

Idlib and its environs are not the only vulnerable areas in Syria. The country as a whole is beaten down by nine years of conflict followed by a grave economic crisis that is threatening the food security of citizens. The Syrian pound has collapsed, making even basic staples too expensive for many families, and poverty and unemployment are rampant with no reconstruction aid expected any time soon. The recent Caesar sanctions imposed by the US against the regime will choke off any remaining lifelines.

As of Tuesday, the Syrian Ministry of Health had confirmed 417 cases of Covid-19, including 19 deaths and 136 recoveries, with the majority being in Damascus and its countryside. There are also cases in the Kurdish-controlled north-east. The mix of restrictions on movement and economic activity that were briefly imposed has cost many people their livelihoods, while the recent lifting of these restrictions is likely to contribute to the spread of the coronavirus. Neither is a scenario that Syria can afford.

But these challenges are even more severe in the displaced and destroyed communities of Idlib. The collapse of the economy and possible coronavirus-related restrictions are going to be much worse for families that have been displaced many times over the course of the war, forced repeatedly to move and find shelter, leaving their lives behind, and for families that overwhelmingly rely on humanitarian aid for food, education and healthcare. Nearly three in every 10 children under five in north-western Syria are stunted because they are chronically underfed.

Lockdowns to combat the spread of infection are likely to have an outsized effect on their livelihoods and make it harder to deliver desperately needed assistance.

They have also had deeply troubling effects on women and children. OCHA says that domestic violence and sexual abuse are on the rise, as are practices such as child labour, early marriage, forced abortion and forced prostitution that bring in some financial relief for desperate families.

So far, just 2,500 Covid-19 tests have been administered in opposition areas. Throughout the country, only 12,000 tests have been administered, which means we have little grasp of the real scale of the pandemic in Syria.

Other countries in the region, including Egypt and Iran, are buckling under the strain of second waves of the coronavirus, unable to control a raging pandemic. Neither country is at war. Outbreaks of such magnitude will be far more devastating in Syria, and we must break the cycle of catastrophes.

Kareem Shaheen is a former Middle East correspondent based in Canada